Two Willie Thornes

I was very sad to hear about the passing of Willie Thorne. As a young man studying at Loughborough University but dreaming of becoming a snooker player at the start of of the Nineties, I regularly played in tournaments at Willie’s club in Leicester. His brother Malcolm, a lovely man, managed the club. Malcolm was a great supporter of pro-am snooker, staging monthly ‘one-dayers’ that regularly attracted 128-plus entrants, including some good pros and some of the best up-and-coming talent in the country. I saw some top-class matches there; occasionally, I played some half-decent stuff as well. Willie’s mum ran the kitchen, serving up Sunday roasts to fuel the players during long tournament days that often stretched long into the evening.

Willie was too well established as a top player by then to play in these events, but he would often glide in during the day, chat with the locals and watch the action.

The Willie Thorne Snooker Centre was unlike any other snooker club I ever played at. It was situated upstairs in a grand old building and the main room had super-high ceilings lending it a cathedral-like atmosphere. Table 1 was Willie’s table, a BCE tournament table, where he practised and had made many 147 breaks. Everyone in the tournaments wanted to play on Willie’s table. There was seating for an audience at either end. On the wall next to it was a massive old-fashioned manual scoreboard and large gilt-framed photos of Willie with the Mercantile Credit Classic trophy. That single major ranking title win was a meagre return for a player of his talent, but he was the undisputed king of Leicester snooker.

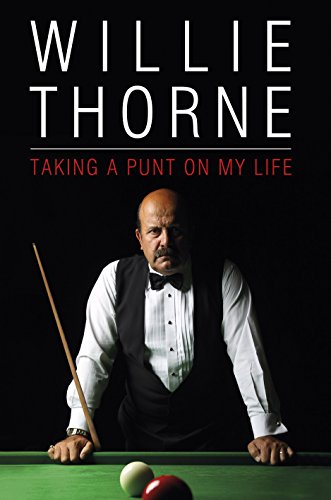

Years later, in early 2011, I was asked to edit Willie’s autobiography, Taking a Punt on my Life. I later went to Leicester to supervise the cover photo shoot back in his old club. He no longer owned it, but his name was still over the door, and memories came rushing back as we set up the balls on the match table for the photographs. Not much had changed; the gilt-framed photos were still there.

In November that year, I met up with him again for an in-depth interview. Here it is…

Two Willie Thornes

He was a leading player in the ‘Snooker Loopy era, but Willie Thorne’s other life as a gambling addict left him bankrupt and suicidal. In a frank interview, he reveals where it all went wrong, how he recovered from the brink and the regrets that still haunt him…

It is eight years since The Sun’s infamous ‘Bonkers Bruno Locked Up’ headline greeted the sectioning of former world heavyweight boxing champion Frank Bruno. Condemnation from mental health charities and the general public swiftly followed, and the newspaper issued an apology and retraction. And yet, recently, Willie Thorne, an ex-snooker player with a near-fatal history of depression, suffered similarly insensitive treatment for which he has received no expression of regret.

The offending article, written by The Mirror’s betting columnist, Derek McGovern, was tucked away on the inside pages of the newspaper. Referring to Thorne’s autobiography, Taking a Punt on My Life — which, ironically, had been serialised in the same paper — McGovern manages to ridicule Thorne’s baldness, weight, gambling addiction, ability as a snooker player, and, most seriously, his attempted suicide. All in the space of 250 words.

Sample ‘jokes’ include: ‘He swallowed aspirin after aspirin in a bid to end it all. But after the first couple, he felt an awful lot better.”

‘Thorne had managed to write a note to wife Jill before taking the pills. “£10 win, first favourite at Pontefract.”’

I’m meeting with Thorne a few days after the article was published. It’s nominally a day off for him after a couple of weeks on the road, but he’s kindly agreed to accommodate me. He collects me from Market Harborough train station near his home and we begin our chat on the drive into Leicester where he is meeting a friend. When we arranged the interview over the phone, he’d mentioned The Mirror piece and when I checked I was surprised to see it still on the newspaper’s website. He admits that he completely lost it when he first read the piece and clearly remains very upset:

“I rang up the news desk and asked for his [McGovern’s] number and they gave me his personal number. Well, I just ripped the biggest strip off him. I was saying, ‘Listen, I’ll give you a fucking slap’ and all this business on the phone. All he could say was that it was supposed to be tongue-in-cheek, but it’s not when you’re talking about someone trying to take their own life.”

Later I refer the article to ‘Time to Change’, a programme run by charities Mind and Rethink Mental Illness, and their statement reinforces Thorne’s view: ‘Time to Change aims to end the stigma surrounding mental health and this comical commentary piece, which makes light of depression and suicide, is not helpful in our fight against the discrimination that people with mental health problems face. According to the Samaritans “Media Guidelines for reporting suicide and self-harm” care should be taken to avoid excessive detail about the method used. References in this article are out of line with these guidelines.’

“There were three or four things he wrote which really hurt,” says Thorne. “Like he talked about my weight. I’m overweight, because since Malc died [his brother Malcolm died of cancer in January] I haven’t felt like going to the gym, so I’ve put two stone on.”

“When the sports editor rang me back later, he said, ‘Look, I was prepared to say sorry, but you’ve just threatened our journalist.’

“I replied, ‘Yeah, I have threatened him. And I will hit him if I fucking see him.’

“But he said the writer had told him I’d threatened to ‘send the boys round’ which I didn’t. I wouldn’t — I’d hit him myself. I’ve never rang up anyone like that before, but what he said about me was the lowest of low. Because of my reaction, they are using that as an excuse not to apologise for the article.”

Such aggression is wildly out of character for this most amiable of men, but anyone who reads Thorne’s memoir will understand his reaction. It is the confessional of a gifted sportsman, one of the most recognisable faces of snooker’s golden era. The book covers the high times when Thorne travelled the world first-class, the womanising which ultimately wrecked his first marriage, and the staggeringly reckless gambling which led to bankruptcy in 1992. As his playing career and earning power declined, the gambling continued unabated, a tax bill of £250,000 landed and a second bankruptcy was only narrowly avoided. Long prone to depressive episodes and consumed by guilt at the continuing deception required to keep the true extent of his gambling from friends and family, in March 2002, a few days after his 48th birthday, Thorne attempted suicide. He recovered physically, but secretly continued to gamble way beyond his means, racking up huge debts to moneylenders charging steepling interest rates.

As his life unravelled once again, Thorne somehow managed to maintain a happy-go-lucky public persona in his post-playing career as a snooker commentator and events host. In the end, after frittering away in excess of £1.5 million, it was only a chance encounter on a golf course which put him on the path to recovery.

I was employed to edit the final manuscript of Thorne’s book and while I had been aware of his gambling issues and suicide bid, I had no idea of the extent of his problems. The text is suffused with deep-seated guilt and lacerating self-criticism: first and foremost, at the pain he has caused loved ones, with his gambling and failings as a husband and father; also at squandering the wealth he acquired at a time when snooker players earned more that top footballers, and not making the most of his natural ability. I wonder if he ever gives himself a break and celebrates his achievements as a player, though? He did, after all, win 14 professional tournaments worldwide.

“I felt I underachieved. Okay, I had some good times and won some tournaments, but I should have done better. I just hate myself for not giving it 100 per cent.”

“Not really. I feel more comfortable being a so-called ‘celeb’ than an ex-snooker player now,” he says. “I felt I underachieved. Okay, I had some good times and won some tournaments, but I should have done better. I just hate myself for not giving it 100 per cent. Loads of times I went to tournaments, under-prepared, under-practised. Late nights before and all that. That is the only regret I have – not giving myself a shot.

“Yes, they were great times for snooker. There were only four television channels, everybody knew the top players. And it was probably down to us lot that we got the game going abroad, so that’s something I’m proud of, yeah. But when I lie in bed at night sometimes, I just wonder if I hadn’t have found gambling and had given it everything like Mark Selby [Leicester snooker pro, currently ranked number one in the world] whether I would have won the world championship.”

But gambling has been an integral part of Thorne’s life since the age of 15 when he first walked into Osborne’s billiards hall, next door to a bookies, in Leicester. It was the sort of place where you if wanted a cheap car or TV you could buy it, no questions asked. Brian Cakebread, the best player at the club who recognised Thorne’s talent and took him under his wing, was a compulsive gambler. And it was here that Thorne soon joined a crew of punters boasting such colourful monikers as ‘Racing Raymond’, ‘Billy The Dip’, ‘Relentless Reg’ and ‘Red-faced Man From Braunston’ who would back him in money matches. Racing Raymond, an on-course bookmaker, introduced Thorne to the atmosphere of a day at the races. He was immediately intoxicated, learning to tic-tac and working for his friend as a clerk.

Meanwhile, Thorne was consistently winning snooker money matches, earning £100-200 apiece at a time when £200 was a good weekly wage, which allowed him to give up his job as an estimator for a local glass firm. Long before he became a professional snooker player, money came easily and any gambling losses on the horses were easily absorbed without affecting his comfortable lifestyle.

“I was always very lucky,” he admits. “I turned pro at 21 and was the youngest pro in the world at the time. So when I was going round the clubs in the Midlands at 17, 18, they would think how can this snotty-nosed kid beat me? I must have won 50 grand over the years in Birmingham – it was like going to the bank for me… Hang on, I want to take you this way… ”

He takes a turn off a roundabout towards the village of Great Glen.

“I want to show you my first house; it was one of the best in Leicestershire. I was the first house here and Englebert [Humperdinck’s house] was the last going out. You’ll see it in a second now… well, if you can see it through the trees.”

After passing alongside a line of unkempt trees and dense undergrowth, Thorne slows the car to a halt opposite a padlocked gate. Down a sweeping driveway lies an impressive house that has fallen into disrepair.

“It’s incredible what’s happened to it,’ he says wistfully. “There were gorgeous gardens… Had a lovely sun lounge on the side. A villain bought it from me. He died and his son owns the place. Just let it completely go…

He restarts the engine: “I can’t believe that, that’s made me feel bad. Not been by here for two or three years… ”

Thorne bought the house when he was one of Britain’s highest-earning sportsmen, and lived here with his first wife, Fiona, and their three children. He admits to being serially unfaithful to Fiona while travelling the snooker circuit, and while she forgave a couple of the affairs she found out about, their marriage crumbled when Willie fell in love with another woman. Concurrently, his gambling was escalating out of control, and he was soon forced to sell the house to pay off debts.

“It was up for £450,000,” he recalls. “I got offered £400,000 the next day but the sale didn’t go through. All of a sudden the property crash happened and I ended up selling for 280.”

The reduced sale price was not enough and he was made bankrupt.

‘He once travelled home from a week in Ireland with around £100,000 in cash — won betting on himself and various horse races — most of which was stuffed in the lining of his Crombie jacket.’

In his book, Thorne recounts times when he would think nothing of staking tens of thousands on a single horse race or a snooker match. He once travelled home from a week in Ireland approximately £125,000 better off, with a cheque for £25,000 for reaching the final of the Irish Masters in his pocket, plus around £100,000 in cash — won betting on himself and various horse races — most of which was stuffed in the lining of his Crombie jacket. Conversely, there was a catastrophic occasion when he bet £38,000 he didn’t have (by tipping other punter friends and asking them to each put bets of £1,000-£1,500 for him as well) on John Parrott losing a match in the Scottish Masters after discovering Parrott had had his cue stolen. Somehow Parrott managed to win with an unfamiliar borrowed cue and Thorne, who was commentating on the match, covered up his horror from the watching millions.

Here, as with all the high-rolling escapades detailed in his memoir which ultimately led to his downfall, what is notable is that Thorne was always acting on an informed tip. There was method in the madness.

“I was never a compulsive gambler,” he contends. “A compulsive gambler, for me, is someone who wants to have a bet every day. Okay, I was a bad gambler, but I would literally not have a bet unless I was told, ‘Put your money on this, it’s good value.’ Never used to back anyone except those who made it pay… unfortunately, I managed to find the times when they were having a bad run! And there are people I used to listen to still gambling today and making fortunes.”

Bad luck is a recurring theme of our conversation. As a player, Thorne was known as player who couldn’t cope mentally with it.

“I was terrible,” he admits. “Especially if someone fluked a ball against me. I hated it. If there wasn’t any bad luck [for me] there wasn’t any luck at all. It used to drive me mad. I’d get them in all sorts of trouble, all of a sudden, two kisses, one drops in, they get an eighty-odd break. I’m thinking what’s all this about. Unbelievable.

“Honestly, if you can look at all the tapes of me playing snooker, if you find two flukes in all the matches you watch, that’s as many as you’ll find. Yet [Steve] Davis, he would have a fluke every match – a telling fluke. Okay, he played more frames than me so you noticed it more…”

But in snooker, when you are on top form you tend to get good luck, right?

“Exactly. You deserve to get it if you play as well he was.”

“Gambling in a snooker club, I never twitched; I was probably one of the best money players in the game.”

For a habitual gambler so used to the vicissitudes of fate, this inability to deal with luck seems strange, but, I suggest, his gambling instincts might have helped cope him with another fundamental part of top-level sport — pressure?

“I was able to cope with it if I had a bet one-on-one. Gambling in a snooker club, I never twitched; I was probably one of the best money players in the game. I must have played 40 money matches in Osbornes and Patsy Fagan [winner of the 1977 UK Championship], who was a great money player, was the only one to beat me.

“But in tournaments, maybe I was looking at the rankings too much. I used to twitch because of that, perhaps. And I wasn’t okay towards the end [of my career] when I had to get to quarter-finals just to pay off debts — that’s a different kind of pressure.

“The finals I lost in were normally to Steve Davis. He was two blacks better than anyone else at the time. He was fantastic. But plenty of times I beat him, and I should have beat him in the UK. But I did twitch a bit there because I backed myself to win a hundred grand in that tournament. In fairness, I was flying at the time…

‘The UK’, he refers to, is the 1985 UK Championship final, the second most important tournament after the World Championship, when Thorne missed a simple pot on the blue against Davis when set to go 14-8 ahead, and ended up losing the match 16-14. Thorne would enjoy other successes in smaller tournaments, but he admits in his book that after that he never quite recovered the fine edge of confidence he began his career with. Some snooker fans retrospectively dismiss him as a ‘bottler’ on the basis of that one shot. Does that annoy him?

“In fairness, all of a sudden, getting over the winning line became a problem for me. There was a weakness. I think if I’d won the UK, I would have been tough to beat for a few years, because I was breakbuilding as good as anyone. No one could score as well and consistently as I could at that time. Obviously, Hendry later took it to another level… ”

“In proper exhibitions, I made over 30 maximums at a time when no-one knew how to make 147s.”

Indeed, Thorne, once known as ‘Mr Maximum’ for his exceptional ability to compile maximum 147 breaks, can rightly claim to be an innovator when it comes to breakbuilding. Today’s top professionals play on heated tables with slick cloths making it easier to manouevre the cue-ball and split packs of reds, and maximum breaks are commonplace, but Thorne learnt his trade on damp, heavy cloths, playing every shot with sidespin to manufacture angles and coax the balls into position.

“I would have loved have to have been around with these conditions. I honestly think I would have won more on these tables and cloths because it’s so easy. When we played at the Crucible for the first ten years, if it was raining outside, the cloth was damp.

“In proper exhibitions, I made over 30 maximums at a time when no-one knew how to make 147s,” he recalls. “John Higgins [four times world champion] didn’t make his first one for a long time because he didn’t play the right shots. It’s about knowing when to move the reds, when not to.

“I will never call a shot wrong when I’m commentating on [Stephen] Hendry and [Ronnie] O’Sullivan because they are the only two players who just see it the way I see it. [Shaun] Murphy’s not bad either. Yet when [Ken] Doherty, John Higgins and Selby build breaks, they play wrong shots as far as making maximums goes. In terms of winning the frame, obviously they play it right, but making 147s is an art and there are only a handful of players who’ve had that art.”

Thorne admits to being “a bit of a poser on the table” and that perhaps his winning instincts were not so acute during his career:

“I wish I knew how important winning was years ago. I love people doing well. I love it when I see people win races or snooker tournaments — I get tears in my eyes. I actually get excited and cry when X Factor’s on and they get to the next round! I enjoy people doing well. I just get a buzz, because I know that’s what they wanted to do.

“The funny thing is that when I did win [the 1985 Mercantile Credit Classic] I didn’t feel anything. Weird. When I lost to Davis to the final of the UK, I was definitely the second best player in the world, but I was never ranked higher than seven. I’d lose to people who couldn’t play.

“I wasn’t like Judd Trump, I didn’t go for everything. I had a bit of craft. But I used to play people and think ‘He can’t beat me’. Then I’d go behind and get nervous. Consequently, people would say I hadn’t the best bottle in the world.”

An over-confident, even unrealistic, attitude is probably a fairer assessment. And perhaps this extended to his gambling. In his book, he talks about how within a couple of years of his bankruptcy, it was business as usual for him except that he was placing “relatively modest bets of two or three thousand”. For all his reliance on tips from knowledgeable insiders, the risks he was taking are beyond the comprehension of most people and ultimately led to his downfall. At times, he held 15-20 accounts with bookies, shifting money around to clear debts, but such were his problems, he also ended up borrowing from friends and family. As we pull into the car park at Leicester train station, I ask if gambling cost him any friendships?

“I’m sure it may have done, but usually if I said I was going to pay money back on the 12th of May or 13th of September, I’d get it together. For years I kept the balls in the air like that. It was impossible, but I did it.

“I’ve never maliciously hurt anybody in my life. I’ve only ever borrowed off people who had plenty of money, so it didn’t make any difference. I’ve paid back money to those I owed to. Obviously, bookmakers, a couple have been left over. A gambling debt’s a debt of honour, y’know, so…

“If I knew that I had ten grand coming in [from snooker] which I could bob and weave with, I just made sure I kept everybody sweet. But when the money wasn’t coming in anymore… I could be sitting here talking like this to you and then going home and sit for hours and hours downstairs, staring into space, thinking what will I do… Listen, I hate myself for doing it. Hate myself.”

“I couldn’t stand anyone thinking bad of me. I’d rather do someone a good turn. I just want to be a nice guy. I didn’t want to hurt anybody. And I did hurt people close to me.”

And that’s perhaps why through all the repeated acts of irresponsibility he admits to in the book, you find yourself pulling for him. It is agonising to read how he repeatedly chose to try to gamble his way out of trouble, rather than confide in people who loved and could help him — most notably, his second wife, Jill, and John Hayes. Jill, a former Miss Great Britain he met while working at the World Championship (“She had already left her husband when I met her, she was at an all-time low, so an ugly twat like me could get involved!”), supported him through his suicide attempt and they were married the following year. Hayes, an old schoolfriend and CEO of Champions UK, who helped Thorne to clear an unpaid £250,000 tax bill and avoid a second bankruptcy, but Thorne still hid his ‘unofficial’ debts from him.

“It was trying to save face,” says Thorne. “I couldn’t stand anyone thinking bad of me. I’d rather do someone a good turn. I just want to be a nice guy. I didn’t want to hurt anybody. And I did hurt people close to me.”

It was this guilt at letting people down which was at the heart of his clinical depression. In the book, he recalls an occasion, in the late Nineties years before his suicide attempt, when he considered jumping from the window of his room near the top of a high-rise hotel in Bangkok. It is therefore surprising that he’s never had any professional counselling for either for depression or his gambling addiction, despite being offered it many times.

“There were two Willie Thornes — I was living a double life. They were dark times and life is better now.”

“I’ve had a chat with a doctor about depression, I was on Prozac for a couple of years, and I must admit I still get depressed now. When the book was published, I did two days of interviews — 18 radio shows on the trot one day. Obviously, I kept talking about the same things over and again and all of a sudden I hate myself again. This past week or so has not been great to be honest.

“Apart from that one article, the coverage was great. But for three or four years, I’ve been okay, getting on with life. I’m not saying I wish I hadn’t done the book, but it has opened wounds again.

“But y’know, it’s letting people know the real truth of what I’ve been through. There were two Willie Thornes — I was living a double life. They were dark times and life is better now.”

Indeed, his life has improved beyond recognition. Participating in the 2007 series of Strictly Come Dancing helped to rebuild his confidence and his public profile. Thorne is now heavily involved in Champions UK (“I’m the ambassador, as it were… ”) clocking up tens of thousands of road and air miles per year to host events, dinners, auctions and golf days. A genuinely warm and friendly person, who likes a laugh and a joke, the work suits him well.

When overseeing the cover shoot for his book, I’d visited his home in Broughton Astley which he shares with Jill, two dogs — Charlie and Alfie — and a great fluffball of a cat called Simba. The house may not be quite as fancy as the Great Glen pile, but it bespeaks a comfortable lifestyle. And with Hayes keeping a close eye on his finances, his future looks secure.

Thorne says he now derives most satisfaction from his work with the Rainbows Children’s Hospice: “I laid the first brick of the new wing for which we had to raise £4 million of which Champions raised over a quarter of a million during the past few years, To see kids there who would love to be a footballer or a snooker player, it makes me feel humble and proud to be their patron.”

He doesn’t play snooker anymore (“My eyes have gone… ”), but he maintains a strong link with the game as a commentator and chats animatedly with me about the current stars of the game such Judd Trump, Mark Selby, Ding Junhui and Shaun Murphy. He talks particularly fondly of Selby, “because he’s a Leicester lad, doing things that I should have done”, and tells me he’s been around to see him at his new house this morning. Their relationship has not always been so cordial though, due to a fall-out between Selby and Willie’s late brother Malcolm.

Malcolm was a much-loved personality in the snooker fraternity. He managed Willie’s snooker club in central Leicester for many years, staging 128-player tournaments and supporting many up-and-coming players along the way, including Selby. “Malcolm had probably spent probably ten or 15 grand on Mark over a few years. Someone offered him an extra few quid per month, and he left Malcolm, just when he’s got half a chance of half getting his money back. It destroyed Malc. Mark in fairness didn’t realise what he’d done to my brother at the time. He’s a nice lad, he was just naive, easily led.

“I’ve never ever been rude to Mark at tournaments, but it wasn’t until Malcolm was dying that I told him why I wasn’t as friendly as perhaps he thought I should have been. Mary [Malcolm’s wife] and mum didn’t even want him to come and see Malc when he was ill. I was, like, give him a chance because they hadn’t really spoke for five or six years. And I’m glad they did. They both had a good cry and made up.”

The death of his beloved brother has hit Thorne hard. It’s clear too that he still has to wrestle with his lingering regrets and innate gambling instincts.

“Yes, I still do the lottery,” he admits, before heading off belatedly to meet his friend. “And if I get a tip that this is a certainty in the 4 o’clock, I might still have two hundred quid on it — I don’t count that as going to change my life.

“I should feel good. But if you said to me, ‘Willie, I’m going to Barbados next week for two weeks, do you want to come?’ I couldn’t come. And I’ve earned fortunes over my lifetime. I should have a house in Spain now. Probably, I still do the lottery because if I do win a million quid, I’d have that house in Spain. So there is still that little thing inside me… ”

END